Carrying Out My Grandpa’s Vision

Finding inspiration through a presidential historian’s belief in the citizen

By Scott Warren

When I tell the origin story of my motivation behind founding Generation Citizen, I talk about growing up abroad as the son of a Foreign Service Officer. I observed democratic elections in Kenya, witnessed a coup in Ecuador, and was in Zimbabwe during violent run-off elections (very much top of mind right now, as the country finally moves past deposed despot Robert Mugabe. Meeting citizens who were willing to risk their lives to pursue democracy, I was convinced of the power of democracy. The power and fragility of a form of governance where people have the ultimate power motivates me to this day.

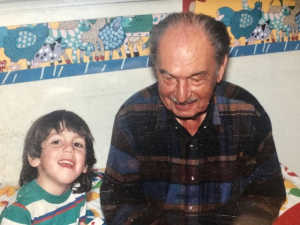

But I neglect to mention another formative part of my passion for democracy: my grandfather, Sidney Warren. He believed in the promise of the American democracy, and the integral role of the citizen in pushing our country to a better place.

My grandpa was a presidential historian, passionate about telling the story of the changing role of the presidency throughout America’s history. He interviewed Harry S. Truman, Herbert Hoover, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Ted Sorensen, amongst other prominent public officials from the time. He wrote five books on the subject, focusing on topics like the emerging role of the president as world leader, and exploring how presidents were elected through regaling stories of campaigns.

My grandfather also became blind at the age of 19. He wrote books even though he was unable to read, with the help of his trusted typewriter, and my grandmother, Sylvia. Being blind still creates so many challenges in our modern world. But surviving, and attempting to thrive, as an intellectual scholar and historian in the mid 20th-century without full use of his vision was trying.

In addition to the challenges of becoming an author without being able to actually read, he was passed over for academic promotions and awards because of his disability. When I’m having a challenging day, and thinking about how hard my job can be, I often reflect on how I literally never heard my grandfather complain about being blind. It was the reality, and so he dealt with it. Ever pragmatic, “it is what it is,” was one of his favorite sayings.

Growing up in San Diego, a half hour drive from my grandparents until I was 8 years old, I was not yet the political wonk I am now. Whenever I visited my grandparents, my grandmother would have read him the sports section that morning, so he could catch up on the latest on the San Diego Padres and Chargers, my main interests at the time (they undoubtedly were playing badly). He never was a sports fan, though. “I don’t understand how you’re such a big fan of teams that have completely new players every year,” he would often tell me. He had a point. Conversations would then inevitably turn to politics with my parents, and I would retreat to the TV room to watch the Padres.

My interests have changed, or at least, I’m more interested in politics (I remain hopelessly a Padres fan). A few weeks ago, at my parents’ home in San Diego, searching for a book to read, I stumbled upon one of his books, “The President as World Leader.” Thinking it could be a little timely, given the ever-evolving role of the United States in the world, and our current president’s unprecedented approach to foreign affairs, I devoured it.

My grandfather describes the gradual, but necessary, evolution of the American president, shifting from a leader focused on domestic affairs, to a truly, unparalleled global leader. He describes Wilson’s technocratic focus on establishing a world order through international treaties and attempting to form the League of Nations. He carefully covers Franklin Roosevelt’s slow journey from neutrality to intervention in World War II. And he ends the book with Kennedy’s entrée into the Cold War and his escalating arms race with the Soviets as part of the US attempting to become a stabilizing force in the midst of the emergence of Soviet communism.

At the same time, however, as I plowed through, it became increasingly clear that my grandfather believed, deeply, in the role of citizen. The ideal president was not a hegemonic leader who unilaterally made decisions on foreign policy, but rather, one who listened to the public, at times heeding their concerns, and at other times, bringing them along. Key to his interpretation of FDR’s eventual entrance into World War II was the public’s initial strong opposition to any sort of intervention. Roosevelt, through his infamous fireside chats, made his case to the American public. According to my grandfather, integral to understanding the growing role of the United States as a global leader is an acceptance and promotion of that role by the American citizenry.

As I finished the book, I realized just how much my grandfather believed in this role and responsibility of citizen in guiding the country forward. Indeed, he ends the entire book with the following:

A profound commitment toward increasing the material resources and strengthening the moral values of the country will spark a similar impulse in the populace. Americans should look for leadership that will be wise, humanitarian, courageous. They should seek a President with the capacity to perceive the direction of the times and capable of guiding the nation in that direction: a person forthright in enunciating principles and ends, able to diagnose contemporary maladies and offer possible means for their solution, and above all, capable of illuminating the profound issues that confront the nation.

As citizens of a democracy, however, the Presidency belongs to them. In the words of John F. Kennedy, “In your hands, my fellow citizens, will rest the success or failure of our cause.” The people must be prepared to make their own commitment.

As I read this last section, I felt that my grandfather was directly speaking to me, and Generation Citizen’s work in attempting to form a more engaged and informed citizenry. Despite his focus on the presidency, his deep belief in the supreme reign of the citizen comes through loud and clear. The citizen, not the president, is the most powerful position to hold.

My grandfather passed away in February of 2008. I wrote the first proposal for Generation Citizen in May of that year. I wish that I could talk to him about our work. I wish that I could talk to him about the current state of American politics. I do think, given these ending words to the book, that he might push me, and all of us, to focus less on the problems in Washington, and more on ourselves. As he says, the presidency does belong to us. Sometimes, we do not act as such.

As I continue the work of Generation Citizen, attempting to strengthen the foundations of our democracy through educating young people to be front and center in our democracy, his words motivate me. The story of our American democracy is one not dominated by historical figures in presidents, but rather, one dominated by an American citizenry that continues to push us towards that more perfect union.

On December 5th, Generation Citizen will begin programming in San Diego, beginning an official partnership with the district. Our training will occur two miles from my grandfather’s home, where we would talk sports, and he would attempt to stir an interested in politics. I only can hope that I am helping to carry out his vision of a citizen-centric democracy.

Generation Citizen is a nonpartisan, 501(c)3 tax exempt organization which does not endorse candidates; our goal is to engage our staff, participants, and stakeholders in political and civic action on issues that matter to them personally and in their communities. The opinions expressed in this blog post are those of the writer alone and do not reflect the opinions of Generation Citizen.