We have a voter participation crisis in the United States – most agree on this.

The US ranks 31st out of 35 OECD countries in voter turnout. In the 2016 election, four out of ten eligible voters did not cast a ballot, similar to the rate in 2012. Turnout in midterm and local elections is consistently far worse. The 2014 midterm turnout was just 36%, a 72-year low. In America’s 30 largest cities, an average of only 23% of eligible citizens vote for mayor.

What is less often acknowledged is that while there are a number of factors that predict voter turnout, there’s one that stands out and could hold the key to long-term solutions: age. If you’re over 30 years old you probably voted in this past presidential election. If you’re 18-29, you probably didn’t.

This has real effects on the policy level. With so few people voting, elected officials and the policies they enact inherently cater to those who participate in elections. Yes, that’s how democracy should work, but it means that policy does not always represent the true will of the people. In the United States, social security remains sacred and unchanged in part because seniors account for an outsized proportion of ballots cast. Young voters in the UK learned the hard way when they overwhelmingly wanted to remain in the European Union, but overwhelmingly chose not to vote in the Brexit referendum.

Any approach to increasing turnout should start with an understanding of who votes, and who doesn’t. This means looking at the voters by age group.

Three points on age as a predictor of voter turnout:

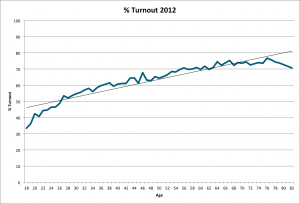

1.) The correlation between age and turnout is well-documented and has been consistent over the years. The 2012 presidential election serves as an illustrative example.

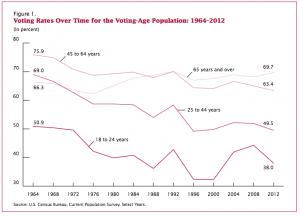

2.) This curve has persisted in election after election for decades, proving that age is indeed the real factor, not generation. As shown in the census bureau’s graph below, while overall turnout has generally declined over the past several decades, the dramatic difference in turnout between younger and older voters has always been clear:

3.) The trend is especially pronounced in local elections, which have perhaps the greatest influence on our day-to-day lives. New data from the Who Votes for Mayor project reveals that:

“Age powerfully trumps all other key factors typically associated with lower turnout, including household income, educational attainment, and race/ethnicity. Even in heavily minority census tracts that contain their cities’ poorest, least educated voters, 65+ voters typically cast ballots at rates 2–5 times more often than 18–34 year olds in that same city’s most affluent and highly educated census tracts.”

The researchers calculate a Generational Electoral Clout metric to measure the extent to which different age groups vote at rates that over- or under-represent their share of the population – in other words, how much younger and older voters punch above or below their weights. The measure shows that in America’s 30 largest cities, citizens over age 65, on average, have seven times more Electoral Clout than 18-34 year olds.

When we think about increasing turnout, we should be thinking about shifting the age curve, so that people don’t wait until they are middle aged to start voting in strong numbers, but vote at the peak rate from the time they are first eligible. This is important because we know that voting is habitual.

Once someone votes for the first time, they are likely to continue voting in subsequent elections. Increasing turnout among 18 and 19 year olds in one election automatically increases turnout among 22 and 23 year olds in the next election, and so on.

While some positive initiatives such as automatic voter registration have shown success, policies and initiatives to increase voter turnout should focus specifically on the youngest eligible voters (ages 18-24). But waiting until they turn 18 is too late: boosting turnout among this population requires engaging with young people before they turn 18.

These efforts can take the form of both structural policy reforms and civic engagement initiatives.

Structural reforms could aim to remove administrative barriers that disproportionately impact youth, like updating addresses and ID requirements. Another example of an effective structural policy reform is 16-year-old pre-registration, which 11 states allow. In these states, citizens can pre-register to vote at age 16, and their registration turns active upon their 18th birthday. Studies on the reform show it has resulted in proven increases in young voter turnout and does not disproportionately favor one party. This works in part because when young people pre-register, they begin to identify as participants rather than outsiders in the political system, which makes them more attuned to politics and more likely to vote.

A more bold policy idea that follows similar logic and deserves serious consideration is extending voting rights to 16- and 17-year-olds for municipal elections. This change has been implemented in two Maryland cities and several countries around the world, and won significant public support as a ballot measure in San Francisco this November. Evidence shows that when given the chance, 16-year-olds are more likely to vote than 18-year-olds. It is a better time to establish voting as a lifelong habit and sets expectations that parents and educators will have more robust conversations with youth about important policy issues.

On the non-policy side, action civics education has a key role to play. Action civics programs like Generation Citizen teach students about politics by having them actually engage with local government while taking action to influence issues they care about. This, too, helps young people embrace their role as participants in democracy and increases their intention to vote when they are first eligible and beyond.

All efforts to increase turnout should be lauded. But, for the greatest impact, we must prioritize solutions that consider, and address, that age is the most important factor in determining voter turnout. We must focus on solutions that reach young people before they are 18, like pre-registration, 16-year-old voting in local elections, and action civics education. This is how we can shift the age curve and create lasting increases in voter participation.